STRANGERS IN OUR STREAMS:

NON-NATIVE AQUATIC SPECIES IN THE SMOKIES

Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSM) is world-renowned-for its biodiversity. The park is home to common, threatened, endangered, and non-native species alike. There are over 70 native and 10 non-native fish, as well as over 8 native and 3 non-native aquatic plants recorded in the park. A-non-native species occurs outside of its native range either by. intentional or accidental introduction. Common introduction pathways of.non-native aquatic species include fishing Sear and vessels, aquarium and live bait releases, waterfowl, and stockings.

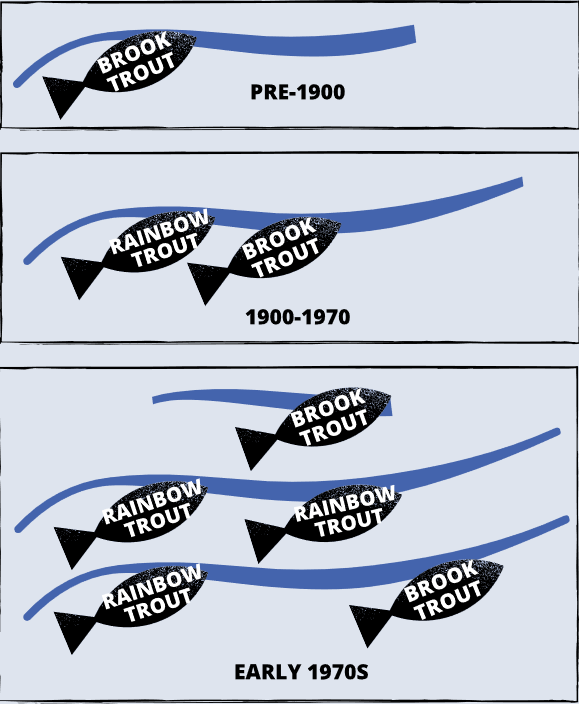

Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalus) are the only native salmon in GRSM. Historically, Brook Trout were found as low as 1600 feet in the Middle Prong of the Little Pigeon River and 2000 feet in the Oconaluftee River. Populations in the park have faced challenges including logging, acid deposition, and the introduction of non-native salmonids. These stressors resulted in a 75% loss of Brook Trout range since 1900/ Initial losses were due to a sedimentation and decreased shade affecting water quality and temperature in park streams, but were compounded by the introduction of non-native salmonids, specifically Rainbow Trout.

It is important to remember that although all invasive species are non-native, not all non-native species are invasive. Some non-native species are actually in high demand, wherether that be for landscaping or sport fishing. The key disctintion is that invasive species are harmful to the environment, economy, or human health. Invasive species outcompete native species. They are a threat to biodiversity and can cause extinction and ecosystem alterations. The terminology gets confusing when words such as ‘alien’, ‘introduced’. ‘non-indigenous’, ‘exotic’, and non-native species, but non-native and invasive are not synonyms.

Various studies in GRSM demonstrated Brook Trout distribution declined until the mid 1980s. Brook Trout occupied less distance and higher elevation streams by 1980 compared to their historic range pre-1900. Streams containing only Brook Trout had decreased from around 98 miles to around 39 miles by the early 1970s. On the other hand, streams containing only Rainbow Trout and both Rainbow Trout and Brook Trout had increased over 58 miles over the same period of time. The average minimum stream elevation for Brook Trout had risen 1500 feet by the early 1970s.

Rainbow Trout have a competitive advantage over Brook Trout that has allowed them to increase their range in the park. The larger body size and weight of Rainbow Trout means they are more likely to secure territory and food. Rainbow Trout are able to withstand stronger currents. Rainbow and Brook Trout occupy similar habitats, but Rainbow Trout can out compete Brook Trout and displace them. Additionally, Rainbow Trout can produce more offspring than Brook Trout.

Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) are another non-native species contributing to declines in Brook Trout. Brown Trout eggs were imported to the United States from Germany in 1883 and released as fry in Michigan by the U.S. Fish Commission, which eventually became part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Since then, Brown Trout have been stocked in nearly every state. They are native to Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. Brown Trout were present in the park by the 1950’s through illegal stocking and stocked populations that migrated from adjacent state waterways. Where Brook and Brown do coexist, there is a unique concern Brook and Brown Torut may hybridize producing a Tiger Trout (female Brown x male Brook) or Leopard Trout (female Brook x male Brown). Both Tiger and Leopard Trout are sterile.